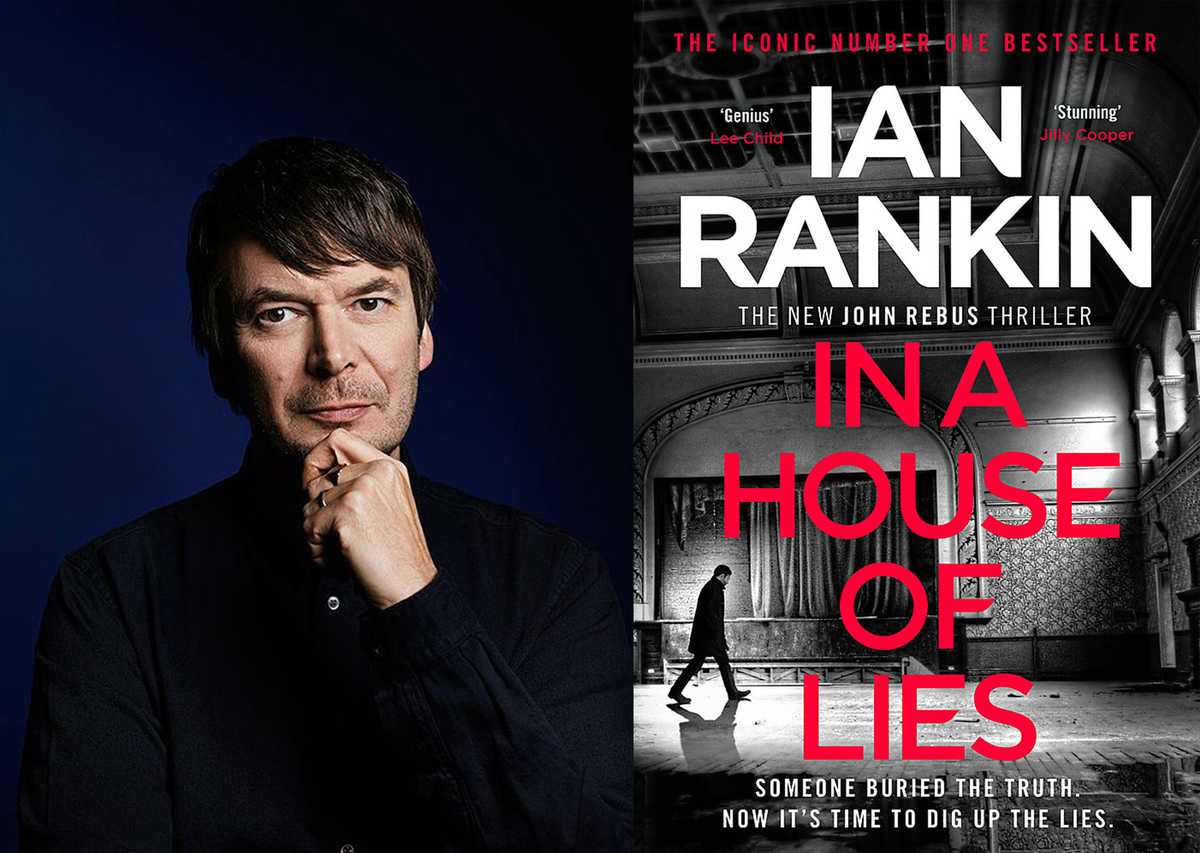

Ian Rankin is one of the most successful contemporary crime writers. He currently lives in Edinburgh with his wife and two sons. His most famous creation, DI John Rebus, has appeared to 21 novels to this day. After Rebus's retirement in 2007, Rankin created Malcolm Fox, who already counts 6 appearances. Ian Rankin has received several awards, including the prestigious Edgar Award in 2004 and Diamond Dagger in 2005, has seen his world inspiring a very successful TV series, and presented his own TV series, Ian Rankin’s Evil Thoughts on Channel 4 in 2002. His latest novel “In A House of Lies” appeared in 2018. Ian Rankin kindly answered our questions about his sources of inspiration, the biggest mistake of his career, Rebus' holidays, his favourite Greek music and many more.

MixGrill: You have found inspiration in long past real events. For example, from the ‘60s serial killer Bible John for “Black & Blue” and from the 19th century Burke and Hare murders for “The Falls”. You have stated that “Saints of the Shadow Bible” was inspired by stories and anecdotes of retired cops, and your latest novel, “In A House of Lies”, by a more recent story that featured in a magazine. Under which conditions can a real crime become source of inspiration? Would you prefer temporal distancing from an atrocious crime (e.g. the murder of six-year-old Alesha MacPhail on the Scottish Isle of Bute in July 2018), that may lead to emotional detachment, yours and of the readers?

IR: I do use real crimes as the basis for some of my books but I also prefer if those crimes took places many years previously – decades in the past if possible. If events are too fresh, I might feel constrained. For example, I wouldn’t want to hurt the feelings of people who were involved in the actual events. So, yes, as you say – I need a certain amount of emotional detachment, the same emotional detachment necessary for a police detective to do his or her job.

MG: Apart from “In A House of Lies”, you also wrote a theatrical play together with Rona Munro. “Rebus: Long Shadows” brought Rebus on stage 30 years after his first adventure. The play premiered in Birmingham in September 2018 and toured in the UK through November 2018, with a new UK tour in the first months of 2019. Unfortunately, I did not have the chance to see the play. I have just read the published rehearsal script. How did it feel seeing Rebus in flesh and blood on stage? What caused the cast change for Rebus, with Ron Donachie replacing Charles Lawson in the 2019 tour?

IR: Rona Munro and I sat down to plot a story that could best be told on stage with actors. We did not want to adapt existing material. My motivation in writing the play was to see Rebus and Cafferty in the flesh, squaring up to one another in a sequence of powerful scenes. I wanted to be in the room with them – this is something I could not get from TV or film. We spent a long time plotting, and then Rona structured the play – she is a professional playwright, so it was easier for her! The events in the play take place in a universe that is parallel to the universe of the books. Not everything is the same. But the characters are still recognisably themselves. The play was a big success, so more theatres wanted it to come to their town or city. But our lead actor had TV commitments, so after the first tour we switched to another actor for the second tour.

MG: Your “In A House of Lies” starts with the discovery of a body from a murder happened some 10 years ago. Indeed, most crime novels include at least one murder. The readers, then, typically follow the course of solving that murder, meaning capturing the culprit. On the other hand, “Nothing solves murder. The dead stay dead”, as reads a phrase that stroke me from “Rebus: Long Shadows”. What is the role of a murder in a crime novel? Could you easily imagine a crime novel without a murder?

IR: I did once write a crime novel (“Doors Open”) that had no murders in it. It was a heist, so there is tension throughout without the need for a central mystery. But murder is still an exceptionally powerful crime – it is the taking away of something unique and irreplaceable from the world. Maybe this is why we writers focus on it. My interest is usually in the ‘why’ – why did this person die? Why do we human beings keep doing terrible things to one another, century after century in culture after culture? This very basic question is at the heart of crime fiction and makes it a form of moral philosophical inquiry. The reader (and the author) becomes the detective, attempting to find answers and in doing so bringing some sense of order to the chaos.

MG: I guess we all have something in our past to regret for or to feel ashamed of. Both “In A House of Lies” and “Rebus: Long Shadows” deal with past sins. Is this just a strategy to activate the long-retired former police officer John Rebus, or is it part of a general introspection period? Which is the biggest mistake of your writing career, after 33 years and more than 40 books?

IR: We find Rebus at a certain point in his life. He is retired. This was forced upon him, because of his age. He is asking himself: do I still matter in the world? Can I still make a difference or a contribution to society? Additionally, he is a detective to his very soul. But now that he is in his mid-60s he is full of uncertainty. His body is failing him; he has medical problems; he cannot intimidate people with his size and demeanour as he once did. And his nemesis Cafferty is in a similar position – yes, he has power, he runs the criminal side of Edinburgh, but for how long? He too is growing old and less threatening and there are plenty of ‘princes’ around him who want his crown. Perhaps these later books reflect my own changing interests as I grow older and my body starts to fail me in ways it didn’t used to. I occasionally regret making Rebus so old in the first book (he was 40) and deciding to age him more or less in real time. But is has also been fascinating to watch him change over time, as I have changed…

MG: Success didn’t come easy at first. But now it is safe to say that you are among the most successful crime writers of all times. You are certainly my favourite one (as you may have guessed). How do you experience the international success? Which is the best thing it has offered you?

IR: It is better to be successful than unsuccessful! But the doubts remain. Will my next book be any good? Do I have anything left to say? Does the police novel interest readers the way it used to or do readers in 2019 want ‘psychological thrillers’ or ‘domestic noir’? Money does nothing to ease these questions! All I can do is what I’ve always done – write my books in order to try to make sense of the world. To make sense of Edinburgh and Scotland, but also to make sense of politics and society and morality and the roots of crime. You also ask me what is the best thing about the success – nice holidays and being able to take a taxi to the Oxford Bar!

MG: In the village where you grew up they have named a street after you. Fast forward to the year 2100. Ian Rankin Chair is established in the Literature Faculty of the University of Edinburgh. Your great-granddaughter publishes her first novel. A PhD student starts researching Ian Rankin's archive, that you recently donated to the National Library of Scotland. The mayor of Edinburgh unveils the John Rebus statue at the neighborhood you currently live. Which of these scenarios would you prefer? Which seems more tempting?

IR: Ah, you are playing the role of Satan – tempting me with hubris! A statue of Rebus would be fun, though I’m not really sure what he looks like. In my early days, I dreamed of becoming a literature lecturer –maybe even one day a professor– so the idea of a Chair at Edinburgh University also appeals to me. The archive is more realistic though. I donated over 20 boxes of material to the National Library of Scotland, and an archivist will spend the next year cataloguing it. It includes unpublished stories and TV scripts, an unpublished novel, early poems, and lots of rejection letters. I am a hoarder by nature, so it’s fairly complete.

MG: Perhaps I should have started with this question. Do you enjoy giving interviews? Is there one specific question you would like to answer but never had the chance so far?

IR: I much prefer written interviews, where I have time to consider my answers and can even go back and edit those answers to make me appear more intelligent and thoughtful than I am when I’m in conversation with the interviewer! But really, I say what I want to say about the world in the pages of my books. They do the talking for me, and they are better at explaining themselves than I am… As for one question I would like to be asked: what was your favourite ever rock concert? But you will need to give me some time to consider my answer.

MG: We live at the time of superheroes and super teams. If (the younger) John Rebus were in such an elite team of "super-police detectives", who would be his companions? And who would be his closer partner?

IR: I suspect Rebus is too much of a loner to work in any kind of team, but he is close in philosophy and working method to a few fictional detectives. I think he would enjoy meeting Lawrence Block’s private eye Matt Scudder – I learned a lot from those books and in fact Cafferty is a homage to the character of Mick Ballou in those books. I also think Rebus and Harry Bosch have had similar career trajectories and life experiences. Both are ex-Army, and now semi-retired. So yes, put Rebus, Bosch and Scudder together for one adventure.

MG: Crime fiction is closely linked with ethics, justice, and law. However, ethical questions have different answers in different time periods. Even justice, that commonly tries to formulate an objective moral correctness, changes over time, e.g., violence against women and child maltreatment. In which context could a crime novel become intertemporal?

IR: It’s interesting that when we consider the nature of evil, we find that the Seven Deadly Sins from the Bible are the most common motivating forces behind the crimes that happened in the past and the crimes that happen today. Slavery is still with us. Psychopaths still walk among us – some of them we celebrate as ‘captains of industry’ or leaders of nations. The best crime fiction has always dug down deep into the core of what makes us human. As the Scottish novelist Muriel Spark once said, we are all capable of great kindness and we are all capable of great iniquity. Sometimes historical events (war for instance) compel us to turn one way instead of the other. Recently, crime fiction has begun to deal with the darker side of social media and the darker side of technological advancement. This is crime fiction’s great strength – it constantly reinvents itself in order to deal with the fears and questions of its audience.

MG: In the past you were writing one book per year. Now it’s one book every two years. Apart from touring, what else do you do in this spare year?

IR: I am as busy as ever! I seem to do more touring, more promotional activities, I get invited to more and more book festivals. And I also get tempting offers to write non-fiction or comic books/graphic novels or plays or film scripts. Plus I am slowing down – it takes me longer to come up with ideas and longer for those ideas to come to fruition as stories I am happy with.

MG: I just have to ask. Are you already working on a new book? Rebus will come back, right?

IR: I have spent the first half of this year preparing to move house and then moving house. We have ‘downsized’ which has been difficult and traumatic. Once things calm down I hope to start work on a new book, maybe in the autumn. I have the first glimmers of a plot and it feels like Rebus is going to be the best person to tell the story…

MG: Rebus and yourself are huge music lovers, with quite similar musical tastes. Your books are brimming with music. In the past you had a punk band, The Dancing Pigs. Since 2017 you participate in a band called Best Picture (listen to their first single “Isabelle”). Along the years, you have also collaborated with Jackie Leven, Aidan Moffat (from Arab Strap), Tim Burgess (from The Charlatans), and Van Morrison. Which artist or band would you like to write a song about Rebus?

IR: Jackie Leven did write a song about Rebus (“The Haunting of John Rebus”). There’s an Edinburgh musician called Blue Rose Code and I would like him to write about Rebus. He is influenced by Van Morrison and John Martyn, which seems perfect.

MG: Have you listened to Greek music? Any favourites?

IR: I don’t know much contemporary Greek music but I am a big fan of Kristi Stassinopoulou and Stathis Kalyviotis. I play ‘Greekadelia’ a lot and got to meet them once in Athens, which was a great thrill for me.

MG: You often visit Greece, especially Kefalonia, but Greece is only rarely mentioned in your books. “In A House of Lies” you sent one of the witnesses in Corfu. What about Rebus visiting Greece with his girlfriend and solving a murder here?

IR: You know, I don’t think Rebus owns a passport. And he definitely doesn’t take holidays in warm countries. But I will be in Kefalonia again this summer and I will be looking for ideas and plots…

Explore our series of articles "Book-Soundtrack"

Read our interview with Tana French

Read our interview with Stuart Neville

Read our interview with the Argentinian crime writer Federico Axat

Read our interview with Tana French

Read our interview with Stuart Neville

Read our interview with the Argentinian crime writer Federico Axat

Relevant article