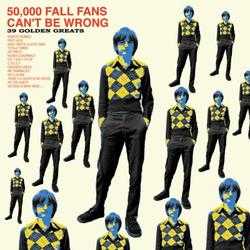

Part of the Manchester scene, the amazing Passage were a part of history in the years of British post-punk period. Personally I like the Passage more than the Fall in quality and value, as they don't have the rough sound of Mark E Smith's band and they "travel" (always in the same way) in electronic paths.

Incredible band! Richard Witts is now a superb musicologist, lecturer in many excellent universities and author of some truly top books. So today I am delighted that he share with us a part of such an important book for Fall exclusively for Mixgrill.

http://www.richardwitts.com/

Chapter One

Building Up a Band:

Music for a Second City

Richard Witts

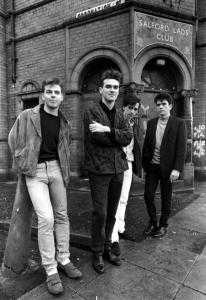

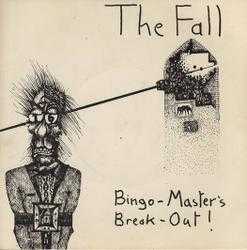

There are many good reasons for writing about The Fall, but I will take the worst. The story of The Fall helps us to understand the post-war history of Manchester where the story of Factory falls short of it. Yet in the five years between 2002 and 2007 there has been a concerted attempt to fix a stiff narrative frame around this city’s musical life. It has been applied by a cartel associated with Factory and keen to raise their ‘heritage’ status in the city’s cultural profile.

There are many good reasons for writing about The Fall, but I will take the worst. The story of The Fall helps us to understand the post-war history of Manchester where the story of Factory falls short of it. Yet in the five years between 2002 and 2007 there has been a concerted attempt to fix a stiff narrative frame around this city’s musical life. It has been applied by a cartel associated with Factory and keen to raise their ‘heritage’ status in the city’s cultural profile.

They have done so in order to delimit general sequences of events around the specificities of Factory Records, its founder the television journalist Tony Wilson (1950–2007), its original club night The Factory (1978–1980) which was succeeded by its nightclub The Haçienda (1982–1997), and the bands associated with the enterprise, chiefly New Order. By constructing and advancing a received post-punk narrative they have swept bands like The Fall out of that history. Yet the stories provided by practitioners and resources such as The Fall, John Cooper Clarke, New Hormones Records, Rabid Records, Band On The Wall, or the Manchester Musicians’ Collective provide much richer accounts of impacts, scenes, activities, realisations and conflicts than the monochrome frame tightly set around Factory.

This retortive campaign grew from the dismay of Factory associates to a general media critique and marginalisation of their venture in the 1990s. Such a reappraisal appeared to precipitate Factory Records’ bankruptcy in 1992 and the decline around that time of the fortunes of the Haçienda club, leading to its closure in 1997 and demolition in 2002. The singer of rival group The Smiths mocked Factory’s parochial character, while the most successful Manchester band of the 1990s, Oasis, had nothing to do with Factory. Sarah Champion’s modish book ‘And God Created Manchester’ (1990) was a flippant survey of the scene that belittled Factory. She wrote of Joy Division’s impact, ‘[y]et even at their peak… hyped to death by writers like Paul Morley, it was nothing compared to the 90s Manc boom.’ (Champion 1990, 11) In contrast, Champion hailed Mark E. Smith as ‘the Robin Hood of alternative pop’ (Champion 1990, 30).

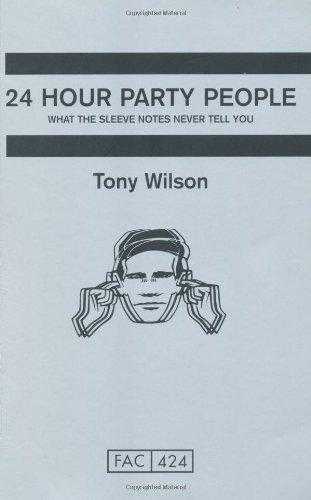

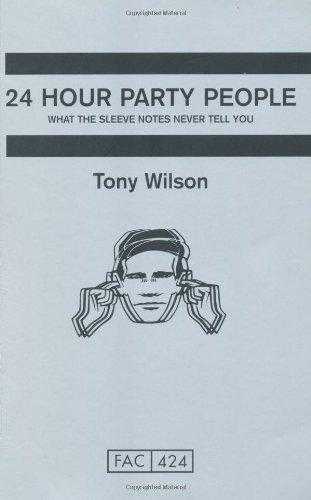

Nevertheless four recent films have stamped the Factory story onto that of Manchester’s. Michael Winterbottom’s fictional 24 Hour Party People (2002) was succeeded by three films which circulated in the same year following Wilson’s death from cancer: Chris Rodley’s documentary Manchester from Joy Division to Happy Mondays (BBC 2007), Anton Corbijn’s Control (2007), and Grant Gee’s documentary Joy Division (2007). Associated with these are no less than five books, chiefly Deborah Curtis’s Touching From A Distance: Ian Curtis and Joy Division (2001), Tony Wilson’s 24 Hour Party People: What The Sleeve Notes Never Tell You (2002), and Mick Middles’ Torn Apart: The Life of Ian Curtis (2007). It is significant how the Factory story that is most being told most loudly is not its near-comical decline (rendered in Winterbottom’s film) but in its place that of the project’s abrupt rise, an ascent associated with the punctuation mark of Curtis’s death. It has been Wilson’s death, however, that has provided the setting for the former to be iconically portrayed.

Nevertheless four recent films have stamped the Factory story onto that of Manchester’s. Michael Winterbottom’s fictional 24 Hour Party People (2002) was succeeded by three films which circulated in the same year following Wilson’s death from cancer: Chris Rodley’s documentary Manchester from Joy Division to Happy Mondays (BBC 2007), Anton Corbijn’s Control (2007), and Grant Gee’s documentary Joy Division (2007). Associated with these are no less than five books, chiefly Deborah Curtis’s Touching From A Distance: Ian Curtis and Joy Division (2001), Tony Wilson’s 24 Hour Party People: What The Sleeve Notes Never Tell You (2002), and Mick Middles’ Torn Apart: The Life of Ian Curtis (2007). It is significant how the Factory story that is most being told most loudly is not its near-comical decline (rendered in Winterbottom’s film) but in its place that of the project’s abrupt rise, an ascent associated with the punctuation mark of Curtis’s death. It has been Wilson’s death, however, that has provided the setting for the former to be iconically portrayed.

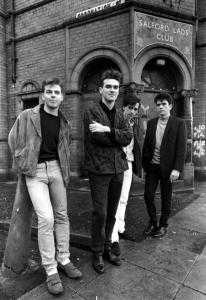

In each of these films the Manchester conurbation of the 1970s is revealed as dilapidated, derelict and deprived. Row upon row of rain-spattered terrace houses are juxtaposed with shots of demolition hammers smashing them down while mucky kids mooch in the rubble. These highly edited images offer a bewildering message; were the people of Manchester and Salford living in caravans parked out the film crew’s sight? The commentaries add to this depressing vista. In Rodley’s film journalist Paul Morley, in an image he must have taken years to hone, talks of how ‘the street lights somehow made things darker, not lighter’. Both Rodley and Gee, fine directors, told me of the limited range of post-war footage available of the conurbation. Most of what is accessible is held in the North West Film Archive. Both directors used a promotional film from its library shot in 1967 for Salford Council, titled The Changing Face of Salford. It is a ‘before’ and ‘after’ portrayal of improvements to the Ordsall area, and the rubble sequences come from the former section. I have made a table of Rodley’s opening shots (Table 1) which lists the sequences. The year of the filming of each segment is shown in the final column, and the whole reveals that Rodley used material shot over two decades to exemplify an impressionistic image of the central 1970s.

Meanwhile Tony Wilson in his book version of 24 Hour Party People set out the premise of the legend that continues to drive the Factory narrative, of how Factory provoked urban renewal:

This was the home of the Industrial Revolution, changing the habits of homo sapiens the way the agrarian revolution had done ten thousand years earlier. And what did that heritage mean? It meant slums. It meant shite… The remnants, derelict working-class housing zones, empty redbrick mills and warehouses, and a sense of self that included loss and pride in equal if confused measures. (Wilson 2002, 14)

In his demotic way he echoes Disraeli who wrote in 1844 that, ‘What Art was to the ancient world, Science is to the modern… Rightly understood, Manchester is as great a human exploit as Athens’ (Disraeli 1948). Having fashioned his trajectory – of how energetic Victorian emprise degenerated into post-industrial inertia – Wilson meshed his big picture with the small when, in Gee’s documentary on Joy Division, he led off, ‘I don’t see this as the story of a rock group. I see it as the story of a city’, adding, ‘The revolution that Joy Division started has resulted in this modern city… The vibrancy of the city and all the things like that are the legacy of Joy Division’, referring finally to ‘The story of the rebuilding of a city that began with them.’ This eschatology is endorsed by Gee’s ‘scriptwriter’ – though there is no script – Jon Savage, who has written an essay to support the documentary in the Spring 2008 edition of Critical Quarterly, where his rather rambling discourse is there to back the inclusion of bleak grey photographs he took of Manchester buildings in 1977 (Savage 2008). It seems the sun never shone when Savage was around.

In his demotic way he echoes Disraeli who wrote in 1844 that, ‘What Art was to the ancient world, Science is to the modern… Rightly understood, Manchester is as great a human exploit as Athens’ (Disraeli 1948). Having fashioned his trajectory – of how energetic Victorian emprise degenerated into post-industrial inertia – Wilson meshed his big picture with the small when, in Gee’s documentary on Joy Division, he led off, ‘I don’t see this as the story of a rock group. I see it as the story of a city’, adding, ‘The revolution that Joy Division started has resulted in this modern city… The vibrancy of the city and all the things like that are the legacy of Joy Division’, referring finally to ‘The story of the rebuilding of a city that began with them.’ This eschatology is endorsed by Gee’s ‘scriptwriter’ – though there is no script – Jon Savage, who has written an essay to support the documentary in the Spring 2008 edition of Critical Quarterly, where his rather rambling discourse is there to back the inclusion of bleak grey photographs he took of Manchester buildings in 1977 (Savage 2008). It seems the sun never shone when Savage was around.

Conversely, let us shine a light on the facts. In the Manchester-Salford complex a period of avid metropolitan modernist planning took place in the 1950s and 1960s, with the objective, first laid out in the 1945 City of Manchester Plan, to eradicate a Victorian heritage of unplanned urban sprawl, one turned to further disarray by momentous wartime damage, and due to which Manchester lacked a vivid civic identity. Instead, the corporation planned a circle of satellite towns in the ‘garden city’ style of 1930s Wythenshawe, the hub for which would be an entirely regenerated city centre of impressive modern offices and prominent civic amenities, a flagship city to compete with other second cities like Chicago, Manchester’s model (HMSO 1995, 11-20).

Meanwhile the post-war pressure for council housing, and the lack of cash and resources had led, instead of garden cities, to a huge inner-city demolition programme. It started in 1954 in parallel with the hurried construction of overspill estates such as Hattersley and Langley (HMSO 1995, 24). Yet the re-housing schemes moved too slowly to meet both national and local objectives. Pressure to find cursory solutions was applied both by Conservative (1951–64) and Labour regimes (1964–70). In the conurbation the Corporation was coerced to produce a hassled second phase outlined in the 1961 Development Plan. Out of this sprouted those inner-city modernist monsters Fort Ardwick, Fort Beswick and the Hulme Crescents, all completed by 1972 and so hastily built that within two years many of the units were uninhabitable (Shapely 2006, 73).

Nevertheless, from the start of the modernist development of Manchester in the middle 1950s ¬until the post-modern shift in the mid-1970s, the vigorous scale of post-war neo-modernist commercial and institutional building resulted in twenty-five major modernist concrete, glass and steel buildings planned and built for the city complex. Table 2 lists these, starting with the surreal ‘Toast Rack’ domestic science college of 1958 (designed by a local civic architect), progressing through the Towers – such as the iconic Co-op of 1962, Owen’s Park 1964, Moberley 1965 and the Maths Tower of 1968 – to the Royal Exchange’s spectacular ‘space pod’ of 1976. This list is not inclusive and excludes, for example, the Arndale Centre, a massive but protracted and piecemeal retail development of the 1970s that was completed only in 1980.

Nevertheless, from the start of the modernist development of Manchester in the middle 1950s ¬until the post-modern shift in the mid-1970s, the vigorous scale of post-war neo-modernist commercial and institutional building resulted in twenty-five major modernist concrete, glass and steel buildings planned and built for the city complex. Table 2 lists these, starting with the surreal ‘Toast Rack’ domestic science college of 1958 (designed by a local civic architect), progressing through the Towers – such as the iconic Co-op of 1962, Owen’s Park 1964, Moberley 1965 and the Maths Tower of 1968 – to the Royal Exchange’s spectacular ‘space pod’ of 1976. This list is not inclusive and excludes, for example, the Arndale Centre, a massive but protracted and piecemeal retail development of the 1970s that was completed only in 1980.

However, many of the new concrete, steel and glass commercial and institutional buildings were neither varied nor coordinated enough to withstand public disapproval, a notorious example being the complex around the Maths Tower, the Precinct Centre, and the Royal Northern College, where the ‘streets in the sky’ walkways were designed at different heights and so couldn’t be connected up. Thus, contrary to the view promoted in the Factory story, the image that Manchester presented to the world was not of a derelict city but a comprehensively modern one – that had got it wrong. In fact, those were the words that Cllr. Allan Roberts, chair of Manchester Council’s Housing Committee expressed in 1977, adding, ‘Manchester’s not been doing its job’. He admitted this after being cornered by burgeoning sets of tenants’ action groups whose campaigns, and the Council’s reactions, are well documented in Peter Shapely’s essay for the journal Social History (Shapely 2006).

The newly formed metropolitan county, the Greater Manchester Council of 1974, identified a clear solution, which materialised as the default post-modern architectural reaction of the period translated to the housing, amenities and image needs of the conurbation: that is, conversion of existing buildings rather than their demolition, identifying conservation areas such as Castlefields, marketing notions of legacy, pedestrianising the city centre, and making the initial attempts within the city of caging modernism within a bricked heritage, firstly and most sensationally at the Royal Exchange Theatre in 1976, and, in that sense following on, the Haçienda of 1982 and, nearby it, both the Cornerhouse visual arts centre and the Greenroom Theatre of 1983. In other words, Factory’s nightclub represented a commercial contribution to a public post-modern design project.

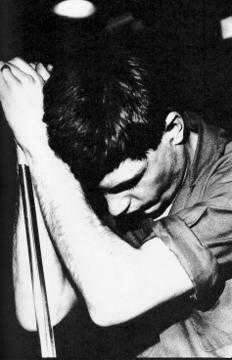

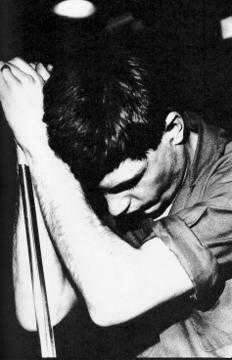

In terms of cityscapes and epochs, then, it appears to be in this post-modern context that we must place the birth of The Fall. Yet if we do so we slip into the same trap in which the Factory story has found itself caught. It is a coarse and quixotic determinism that conjures up the grids and correspondences needed to bond building sites and bands, civic plans and popular songs in the way that the Factory faction has done. The Fall certainly emerged – as did Joy Divison – from a set of circumstances tied to urban environment and class, but not wreckage and squalor. And in strictly musical terms we find in the births of these bands continuities from beyond the punk scene, such as Ian Curtis’s ‘German’ look and Smith’s Beat style (the bass of The Fall’s founder, Tony Friel, was called Jaco, after the jazz bassist Pastorius). Nevertheless, if we are to test whether Factory’s modernist claims suit the times, we must check how far a modernist aesthetic was already present in the city’s music scene. We can indeed identify bands spawned in the area at the time of the late 1960s that were progressive, utopian and internationalist in tendency: Barclay James Harvest, Van der Graaf Generator, 10cc. The short mid-1970s punk scene was definitely a cartoon-like negation of groups like them. But in reaction to that, the effervescent post-punk scene was in general more integrative, tending to mesh convention – such as song form – with experimentation, and to link punk’s gestural Luddism with a progressive curiosity for technology and sound production (on stage and in the studio). In the end it might be claimed that Van Der Graaf Generator’s appearance at University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology on 8 May 1976 was more influential to local post-punk aesthetics than the Sex Pistols’ two gigs at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on 4 June and 20 July of that year, (see Nolan 2006).

In terms of cityscapes and epochs, then, it appears to be in this post-modern context that we must place the birth of The Fall. Yet if we do so we slip into the same trap in which the Factory story has found itself caught. It is a coarse and quixotic determinism that conjures up the grids and correspondences needed to bond building sites and bands, civic plans and popular songs in the way that the Factory faction has done. The Fall certainly emerged – as did Joy Divison – from a set of circumstances tied to urban environment and class, but not wreckage and squalor. And in strictly musical terms we find in the births of these bands continuities from beyond the punk scene, such as Ian Curtis’s ‘German’ look and Smith’s Beat style (the bass of The Fall’s founder, Tony Friel, was called Jaco, after the jazz bassist Pastorius). Nevertheless, if we are to test whether Factory’s modernist claims suit the times, we must check how far a modernist aesthetic was already present in the city’s music scene. We can indeed identify bands spawned in the area at the time of the late 1960s that were progressive, utopian and internationalist in tendency: Barclay James Harvest, Van der Graaf Generator, 10cc. The short mid-1970s punk scene was definitely a cartoon-like negation of groups like them. But in reaction to that, the effervescent post-punk scene was in general more integrative, tending to mesh convention – such as song form – with experimentation, and to link punk’s gestural Luddism with a progressive curiosity for technology and sound production (on stage and in the studio). In the end it might be claimed that Van Der Graaf Generator’s appearance at University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology on 8 May 1976 was more influential to local post-punk aesthetics than the Sex Pistols’ two gigs at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on 4 June and 20 July of that year, (see Nolan 2006).

Existent co-ordinates in the mid-Seventies air informed this post-punk integrative disposition. One such co-ordinate was the resurgent folk music scene of that time, through which singer-comedians such as Mike Harding and Bob Williamson propelled the Lancashire accent. Yet the conscious assertion of a local lingo, in line with the emergent promotion of a heritage culture, turned to deep embarrassment amongst progressive minds with the national success in April 1978 of Brian and Michael’s glutinous homage to local painter L.S. Lowry, ‘Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs’, and, while Ian Curtis of Joy Division maintained his affected American brogue in order to summon ghosts, others, like Mark E. Smith, gradually adopted ironised or embroidered accents, not in order to ‘represent’, but to stress the exceptional act of performance. Nevertheless, in 1978, Paul Morley would excitedly review in the New Musical Express (NME) a Manchester Musicians’ Collective gig under the headline, ‘These are the Mancunion Mancunions’, (see Morley 1978)

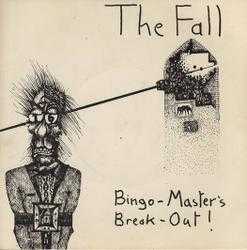

And when the conurbation started to re-assess its matchstalk inheritance it found, inside its dilapidated warehouses, post-punk musicians already there, practising. In ‘renting the heritage’, they were doing little for their health in those dank, freezing echo chambers, but they were working there together in order to prepare for gigs in old buildings such as The Squat (a derelict music college) or dishevelled clubs with dog-eared music licenses such as the Cyprus Tavern and the Russell Club. Rehearsal rooms, 4-track studios such as Graveyard and Revolution, the ‘gentle giant’ tour manager Chas Banks, Oz PA Hire, promoter Alan Wise and Rabid Records were all part of the micro music industry that sprang up in a state of alternative enterprise, in which Factory acted out the role of Icarus. It was New Hormones, run by the non-Mancunion Richard Boon, that did succeed and which gave The Fall its start in a recording studio. Factory was not the brightest thread in the skein of yarns spun about those times.

And when the conurbation started to re-assess its matchstalk inheritance it found, inside its dilapidated warehouses, post-punk musicians already there, practising. In ‘renting the heritage’, they were doing little for their health in those dank, freezing echo chambers, but they were working there together in order to prepare for gigs in old buildings such as The Squat (a derelict music college) or dishevelled clubs with dog-eared music licenses such as the Cyprus Tavern and the Russell Club. Rehearsal rooms, 4-track studios such as Graveyard and Revolution, the ‘gentle giant’ tour manager Chas Banks, Oz PA Hire, promoter Alan Wise and Rabid Records were all part of the micro music industry that sprang up in a state of alternative enterprise, in which Factory acted out the role of Icarus. It was New Hormones, run by the non-Mancunion Richard Boon, that did succeed and which gave The Fall its start in a recording studio. Factory was not the brightest thread in the skein of yarns spun about those times.

Much of the city music scene, even Factory through its proclivity for Situationism, was driven by political critique, and in the experience of many the most class-conscious of all of the bands was The Fall. It always passed a common litmus test for the worth of a band at the time: would it play for free for Rock Against Racism? It would, but Mark E. Smith and Una Baines often stressed that what they believed in formed the content of their work and was not to be confined to a slogan on a banner, for The Fall was critical of both the state we were then leaving and the state that was arriving, and it has remained an agent of broad (as well as picky) critique, the general target of which is, as Smith put it as recently as 26 April 2008 to the Daily Telegraph, ‘the threat of some kind of standardised horrible society run by a bunch of fucking wankers’ (Blincoe 2008).

The vigour and width of this critique surely explains the richness of the material produced in the music and also in the lyrics, and accounts for its range between simplicity (‘Repetition’) and density (‘Spectre versus Rector’), which informs the entire wayward output of the last thirty years. I emphasise music here because composer Trevor Wishart and I in the Manchester Musicians’ Collective loved the music of the band, especially the dissonance achieved through three means – tuning, bitonality, and looseness of co-ordination. The understandable tendency for reviewers to focus on Mark’s lyrics unduly subordinates the sound world in which they’re set, and discounts the musicians who contribute so much to the fabric of the experience. After all, The Fall is a band that plays songs. What fascinated Trevor and me was the way that those songs were not so much constructed as discovered, realised by the members working out through time random ideas that were connected only by the presence of the people in the room at that moment.

The vigour and width of this critique surely explains the richness of the material produced in the music and also in the lyrics, and accounts for its range between simplicity (‘Repetition’) and density (‘Spectre versus Rector’), which informs the entire wayward output of the last thirty years. I emphasise music here because composer Trevor Wishart and I in the Manchester Musicians’ Collective loved the music of the band, especially the dissonance achieved through three means – tuning, bitonality, and looseness of co-ordination. The understandable tendency for reviewers to focus on Mark’s lyrics unduly subordinates the sound world in which they’re set, and discounts the musicians who contribute so much to the fabric of the experience. After all, The Fall is a band that plays songs. What fascinated Trevor and me was the way that those songs were not so much constructed as discovered, realised by the members working out through time random ideas that were connected only by the presence of the people in the room at that moment.

It is for this reason that I persist in calling The Fall a band, meaning that a band is a team of musicians singled out by a corporate name. The individual identities of the musicians contribute to the integrity of the overall sound, but those identities are of less interest than the aural result. A band is closer to, say, Manchester’s Hallé Orchestra, which will take in deputies and visiting players, while the audience, so long as expectations are satisfied, will consider it’s heard the Hallé at 100%, not 90%. Conversely, I consider a group to be an assembly of named personalities, who work together but may individually harbour creative ventures. When a group loses a member, it often has difficult in finding a replacement who will satisfy an audience of the group’s fresh integrity. Perhaps The Rolling Stones was the first British rock band to become a group, prompted by the maverick behaviour of Brian Jones, while The Fall is a band that’s stayed a band. A tension arises between a band mediated as an entity and the needs of the media to attend to it within the conventional expressions of personality. The person in a position to assume identity on behalf of the band is not necessarily the one in control but the one who can most directly presume authority.

Control is achieved because the band is an entity (as one thing) and it can therefore be framed conceptually (as one thing), and it is through this framing that power is claimed and asserted. In a band it is commonly the person physically closest to the public, the one who takes and needs the least internal co-ordination, the fewest cues.

Control is achieved because the band is an entity (as one thing) and it can therefore be framed conceptually (as one thing), and it is through this framing that power is claimed and asserted. In a band it is commonly the person physically closest to the public, the one who takes and needs the least internal co-ordination, the fewest cues.

Smith has alleged in his 2008 autobiography, that ‘They [the band] didn’t want to be in The Fall. The whole concept of The Fall back then was mine. They didn’t get it. The audience did, but not them’ (Smith 2008, 46). In fact its bass player, Tony Friel, started The Fall in 1976. Friel resigned on a matter of principle around Xmas 1977 when Mark introduced his new girlfriend, Kay Carroll, as the band’s manager. The result was that the singer took control, turning a once collective venture into a business enterprise under his leadership.

It is this sense of entrepreneurism that most chimes with Manchester’s recent history, one which might be crudely termed the Thatcherisation of the city. Manchester’s Labour-led administration was a target of the (1979–1990) Thatcher government’s plan Streamlining the Cities (1983) which resulted in the 1986 abolition of the Greater Manchester Council and in its place a directive to elevate economic dynamism through the privatisation of resources which in turn would generate competition in services, a formulation known as ‘entrepreneurial urbanism’ (Ward 2003, 116; Williams 2003, 53- 56). This was a move from government to governance, an ideology that New Labour in power (1997–) persisted with as eagerly as the Conservatives (1979–1997). But it was also designed to impel an assertive urban consumption economy, one which measured prosperity by possessions and which emerged forcefully through the flowering of two related reactionary phenomena in the late 1980s and 1990s – ‘Madchester’, ‘laddism’ – focussed around the leisure market, mainly in football, alcohol and drugs, and epitomised in the local music scene first by Factory’s band The Happy Mondays and then supremely by Oasis. Tickell and Peck point out how the privatising shift of power from elected local authorities to business-led bodies led to the naturalisation of male power ‘as the legitimate conduit for effective local governance’ (Tickell & Peck 1996, 595), signifying how far the story of the Manchester conurbation’s apparent resurgence may be read as a reversionary one. There are no happy women in the Factory story.

Indeed, a return to aggressive neo-modernism that so strongly symbolised rejuvenation and success for the Manchester conurbation may explain the surge of high-rise concrete and glass buildings around the city complex, a style derided by Smith as ‘glorified fridge boxes’ (Smith 2008, 98). Most noticeable among them is the 47-storey Beetham Tower (2006) and Great Northern Tower (2007) among a quasi-modernist resurgence of civic and business showpieces that followed in the wake of the IRA bombing of the Arndale Centre in 1996. The picture is somewhat complicated by, firstly, the introduction of urban grant-aid from the European Union (Bridgewater Hall, 1996) and the advent in 1993 of the National Lottery, which, as a result of campaigns by the architecture profession, offered millions of pounds for new building in sport, heritage and the arts, benefiting major projects in East Manchester and Salford Quays such as the Lowry Centre (2000) and the Imperial War Museum North (2002). Overall, then, Manchester has returned to its modernist mission after a post-modern digression of which Factory played a part. Whether this time the conurbation has got it right rather than wrong, it is too early to say.

Indeed, a return to aggressive neo-modernism that so strongly symbolised rejuvenation and success for the Manchester conurbation may explain the surge of high-rise concrete and glass buildings around the city complex, a style derided by Smith as ‘glorified fridge boxes’ (Smith 2008, 98). Most noticeable among them is the 47-storey Beetham Tower (2006) and Great Northern Tower (2007) among a quasi-modernist resurgence of civic and business showpieces that followed in the wake of the IRA bombing of the Arndale Centre in 1996. The picture is somewhat complicated by, firstly, the introduction of urban grant-aid from the European Union (Bridgewater Hall, 1996) and the advent in 1993 of the National Lottery, which, as a result of campaigns by the architecture profession, offered millions of pounds for new building in sport, heritage and the arts, benefiting major projects in East Manchester and Salford Quays such as the Lowry Centre (2000) and the Imperial War Museum North (2002). Overall, then, Manchester has returned to its modernist mission after a post-modern digression of which Factory played a part. Whether this time the conurbation has got it right rather than wrong, it is too early to say.

If my remark about Thatcherization and entrepreneurism suggests that Smith is a free market kind of guy, then it needs correcting. He criticised the selfishness of her era, arguing, ‘Thatcher’s an antagonist… but people voted her in for their own greed, all looking at rewards’ (Ford 2002a, 97). Yet he supported that side of Thatcher’s project that promoted an ethic for gainful work as a personal obligation, as opposed to a unionised one (an undeniable irony in Thatcher’s case, as her policies were the cause of dramatically high unemployment). In his autobiography he declares: ‘The more you make of your life, then the more you fucking do… Thomas Carlyle, the Scottish writer, said, “Produce, produce – it’s the only thing you’re there for.” This is what I’m talking about’ (Smith 2008, 32). Smith adds that he has a ‘very desk-job attitude’ to The Fall (Smith 2008, 32). Here the ideological link is rooted more to ‘old’ Labour principles which through its very title promotes the centrality of the concept of productive endeavour.

Above all Smith embodies the ‘Old’ working class disposition of the autodidact, who, as Bourdieu states, ‘has not acquired his culture in the legitimate order established by the educational system’ and is ‘fundamentally defined by a reverence for culture which was induced by abrupt and early exclusion’ (Bourdieu 1984, 328). And in his splendid account of British working class intellectual life, Jonathan Rose adds that in order ‘to become individual agents in framing an understanding of the world’ autodidacts ‘resisted ideologies imposed from above.’ (Rose 2001, 12) They did so, as did Smith, by reading and arguing, and out of the reading came the writing. Smith’s interest in esoterica reflects autodidacticism, and his late-teen discovery of another performing/writing Smith, Patti – together with the general rehabilitation at that time of her Beat forebears, such as William Burroughs whose cut-up technique inspired the Lancashire Smith – came about just as a resurgence of radical individual anarchism superseded communal leftist campaigning such as Rock Against Racism. He is not quite the Manchester one-off he is portrayed: the wonderful cartoonist Ray Lowry and cyber-novelist Jeff Noon spring to mind, in those days good drinkers like Smith. Yet his achievement in gathering information, gaining knowledge, and placing it imaginatively back into public space is undeniable, while his lyrics that comment on and describe issues around mental health, linked to the patients he knew at Prestwich Hospital, are unique and significant. Smith’s approach is doubtless informed by the way post-war Beat ideology dismissed modernist utopianism and replaced it with a voyeuristic interest in the ‘real life’ routines of the outlawed and the disenfranchised. The Beat aesthetic further accounts for The Fall’s confluence of experimentation (a very Beat ‘living the moment’) with its default garage band style, one clearly influenced by The Velvet Underground, another Beat-influenced band that chopped and changed its members.

Above all Smith embodies the ‘Old’ working class disposition of the autodidact, who, as Bourdieu states, ‘has not acquired his culture in the legitimate order established by the educational system’ and is ‘fundamentally defined by a reverence for culture which was induced by abrupt and early exclusion’ (Bourdieu 1984, 328). And in his splendid account of British working class intellectual life, Jonathan Rose adds that in order ‘to become individual agents in framing an understanding of the world’ autodidacts ‘resisted ideologies imposed from above.’ (Rose 2001, 12) They did so, as did Smith, by reading and arguing, and out of the reading came the writing. Smith’s interest in esoterica reflects autodidacticism, and his late-teen discovery of another performing/writing Smith, Patti – together with the general rehabilitation at that time of her Beat forebears, such as William Burroughs whose cut-up technique inspired the Lancashire Smith – came about just as a resurgence of radical individual anarchism superseded communal leftist campaigning such as Rock Against Racism. He is not quite the Manchester one-off he is portrayed: the wonderful cartoonist Ray Lowry and cyber-novelist Jeff Noon spring to mind, in those days good drinkers like Smith. Yet his achievement in gathering information, gaining knowledge, and placing it imaginatively back into public space is undeniable, while his lyrics that comment on and describe issues around mental health, linked to the patients he knew at Prestwich Hospital, are unique and significant. Smith’s approach is doubtless informed by the way post-war Beat ideology dismissed modernist utopianism and replaced it with a voyeuristic interest in the ‘real life’ routines of the outlawed and the disenfranchised. The Beat aesthetic further accounts for The Fall’s confluence of experimentation (a very Beat ‘living the moment’) with its default garage band style, one clearly influenced by The Velvet Underground, another Beat-influenced band that chopped and changed its members.

Mention of the Velvets connects The Fall with Joy Division, which the Factory story does not permit, although Ian Curtis was almost as much the autodidact as Smith. The Factory story so flattens Manchester that only the Factory and its tenants are left standing. Yet, as Wilson’s beloved Situationists declared, ‘Beneath the pavements – the beach!’ It is through the rubble of what is left, once the Factory story has been foisted on us as the received narrative, that The Fall and the others will provide, as an alternative, the richest, most potent, most kinetic history of that city. As I said, this is the worst possible reason for writing about The Fall, and so I am sorry for wasting your time.

References

Bourdieu, P. ([1979] 1984), Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Translated by R. Nice, (London: Routledge).

Blincoe, N. (2008), ‘Mark E Smith: Wonder and Frightening’, Daily Telegraph

markesmith26.xml>

Carlyle, T. ([1832] 2000), Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Champion, S. (1990), And God Created Manchester (Manchester: Wordsmith).

Disraeli, B. ([1848] 1948), Coningsby, or the New Generation (London: London Edition).

Ford, S. (2002a), Hip Priest: the story of Mark E. Smith & The Fall (London: Quartet Books).

____, (2002b), ‘Primal Scenes’, The Wire, No. 219, May, 28-33.

Hetherington, K. (2007), ‘Manchester’s URBIS’, Cultural Studies, Vol. 21, Nos 4-5, September, 630-649.

HMSO (1995), Manchester, Fifty Years of Change: Post-War Planning in Manchester (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office).

Morley, P. (1978), ‘These are the Mancunion Mancunions’, NME, 1 September, 25.

Nolan, D. (2006), I Swear I Was There: The Gig That Changed the World (Church Stretton: Independent Music Press).

Rose, J. (2001), The Intellectual History of the British Working Classes (London: Yale University Press).

Savage, J. (2008), ‘The Things That Aren’t There Anymore’, Critical Quarterly Vol. 50, Nos.1-2, 180-197.

Shapely, P. (2006), ‘Tenants Arise! Consumerism, Tenants and the Challenge to Council Authority in Manchester, 1968-92’, Social History, Vol. 31, No.1, 60-78.

Smith, M. E. (2008), Renegade: The Life and Tales of Mark E. Smith (London: Viking).

Tickell, A. & Peck, J. (1996), ‘The Return of the Manchester Men: Men’s Words and Men’s Deeds in the Remaking of the Local State’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 21, No. 4, 595-616.

Wilson, A. (2002), 24 Hour Party People: What The Sleeve Notes Never Tell You (London: Channel 4 Books).

Ward, K. (2003), ‘Entrepreneurial Urbanism’, Area, Vol. 35, No. 2, 116-127.

Williams, G. (2003), The Enterprising City Centre: Manchester’s Development Challenge (London, Taylor & Francis).

Incredible band! Richard Witts is now a superb musicologist, lecturer in many excellent universities and author of some truly top books. So today I am delighted that he share with us a part of such an important book for Fall exclusively for Mixgrill.

http://www.richardwitts.com/

Building Up a Band:

Music for a Second City

Richard Witts

There are many good reasons for writing about The Fall, but I will take the worst. The story of The Fall helps us to understand the post-war history of Manchester where the story of Factory falls short of it. Yet in the five years between 2002 and 2007 there has been a concerted attempt to fix a stiff narrative frame around this city’s musical life. It has been applied by a cartel associated with Factory and keen to raise their ‘heritage’ status in the city’s cultural profile.

There are many good reasons for writing about The Fall, but I will take the worst. The story of The Fall helps us to understand the post-war history of Manchester where the story of Factory falls short of it. Yet in the five years between 2002 and 2007 there has been a concerted attempt to fix a stiff narrative frame around this city’s musical life. It has been applied by a cartel associated with Factory and keen to raise their ‘heritage’ status in the city’s cultural profile.They have done so in order to delimit general sequences of events around the specificities of Factory Records, its founder the television journalist Tony Wilson (1950–2007), its original club night The Factory (1978–1980) which was succeeded by its nightclub The Haçienda (1982–1997), and the bands associated with the enterprise, chiefly New Order. By constructing and advancing a received post-punk narrative they have swept bands like The Fall out of that history. Yet the stories provided by practitioners and resources such as The Fall, John Cooper Clarke, New Hormones Records, Rabid Records, Band On The Wall, or the Manchester Musicians’ Collective provide much richer accounts of impacts, scenes, activities, realisations and conflicts than the monochrome frame tightly set around Factory.

This retortive campaign grew from the dismay of Factory associates to a general media critique and marginalisation of their venture in the 1990s. Such a reappraisal appeared to precipitate Factory Records’ bankruptcy in 1992 and the decline around that time of the fortunes of the Haçienda club, leading to its closure in 1997 and demolition in 2002. The singer of rival group The Smiths mocked Factory’s parochial character, while the most successful Manchester band of the 1990s, Oasis, had nothing to do with Factory. Sarah Champion’s modish book ‘And God Created Manchester’ (1990) was a flippant survey of the scene that belittled Factory. She wrote of Joy Division’s impact, ‘[y]et even at their peak… hyped to death by writers like Paul Morley, it was nothing compared to the 90s Manc boom.’ (Champion 1990, 11) In contrast, Champion hailed Mark E. Smith as ‘the Robin Hood of alternative pop’ (Champion 1990, 30).

Nevertheless four recent films have stamped the Factory story onto that of Manchester’s. Michael Winterbottom’s fictional 24 Hour Party People (2002) was succeeded by three films which circulated in the same year following Wilson’s death from cancer: Chris Rodley’s documentary Manchester from Joy Division to Happy Mondays (BBC 2007), Anton Corbijn’s Control (2007), and Grant Gee’s documentary Joy Division (2007). Associated with these are no less than five books, chiefly Deborah Curtis’s Touching From A Distance: Ian Curtis and Joy Division (2001), Tony Wilson’s 24 Hour Party People: What The Sleeve Notes Never Tell You (2002), and Mick Middles’ Torn Apart: The Life of Ian Curtis (2007). It is significant how the Factory story that is most being told most loudly is not its near-comical decline (rendered in Winterbottom’s film) but in its place that of the project’s abrupt rise, an ascent associated with the punctuation mark of Curtis’s death. It has been Wilson’s death, however, that has provided the setting for the former to be iconically portrayed.

Nevertheless four recent films have stamped the Factory story onto that of Manchester’s. Michael Winterbottom’s fictional 24 Hour Party People (2002) was succeeded by three films which circulated in the same year following Wilson’s death from cancer: Chris Rodley’s documentary Manchester from Joy Division to Happy Mondays (BBC 2007), Anton Corbijn’s Control (2007), and Grant Gee’s documentary Joy Division (2007). Associated with these are no less than five books, chiefly Deborah Curtis’s Touching From A Distance: Ian Curtis and Joy Division (2001), Tony Wilson’s 24 Hour Party People: What The Sleeve Notes Never Tell You (2002), and Mick Middles’ Torn Apart: The Life of Ian Curtis (2007). It is significant how the Factory story that is most being told most loudly is not its near-comical decline (rendered in Winterbottom’s film) but in its place that of the project’s abrupt rise, an ascent associated with the punctuation mark of Curtis’s death. It has been Wilson’s death, however, that has provided the setting for the former to be iconically portrayed. In each of these films the Manchester conurbation of the 1970s is revealed as dilapidated, derelict and deprived. Row upon row of rain-spattered terrace houses are juxtaposed with shots of demolition hammers smashing them down while mucky kids mooch in the rubble. These highly edited images offer a bewildering message; were the people of Manchester and Salford living in caravans parked out the film crew’s sight? The commentaries add to this depressing vista. In Rodley’s film journalist Paul Morley, in an image he must have taken years to hone, talks of how ‘the street lights somehow made things darker, not lighter’. Both Rodley and Gee, fine directors, told me of the limited range of post-war footage available of the conurbation. Most of what is accessible is held in the North West Film Archive. Both directors used a promotional film from its library shot in 1967 for Salford Council, titled The Changing Face of Salford. It is a ‘before’ and ‘after’ portrayal of improvements to the Ordsall area, and the rubble sequences come from the former section. I have made a table of Rodley’s opening shots (Table 1) which lists the sequences. The year of the filming of each segment is shown in the final column, and the whole reveals that Rodley used material shot over two decades to exemplify an impressionistic image of the central 1970s.

Meanwhile Tony Wilson in his book version of 24 Hour Party People set out the premise of the legend that continues to drive the Factory narrative, of how Factory provoked urban renewal:

This was the home of the Industrial Revolution, changing the habits of homo sapiens the way the agrarian revolution had done ten thousand years earlier. And what did that heritage mean? It meant slums. It meant shite… The remnants, derelict working-class housing zones, empty redbrick mills and warehouses, and a sense of self that included loss and pride in equal if confused measures. (Wilson 2002, 14)

In his demotic way he echoes Disraeli who wrote in 1844 that, ‘What Art was to the ancient world, Science is to the modern… Rightly understood, Manchester is as great a human exploit as Athens’ (Disraeli 1948). Having fashioned his trajectory – of how energetic Victorian emprise degenerated into post-industrial inertia – Wilson meshed his big picture with the small when, in Gee’s documentary on Joy Division, he led off, ‘I don’t see this as the story of a rock group. I see it as the story of a city’, adding, ‘The revolution that Joy Division started has resulted in this modern city… The vibrancy of the city and all the things like that are the legacy of Joy Division’, referring finally to ‘The story of the rebuilding of a city that began with them.’ This eschatology is endorsed by Gee’s ‘scriptwriter’ – though there is no script – Jon Savage, who has written an essay to support the documentary in the Spring 2008 edition of Critical Quarterly, where his rather rambling discourse is there to back the inclusion of bleak grey photographs he took of Manchester buildings in 1977 (Savage 2008). It seems the sun never shone when Savage was around.

In his demotic way he echoes Disraeli who wrote in 1844 that, ‘What Art was to the ancient world, Science is to the modern… Rightly understood, Manchester is as great a human exploit as Athens’ (Disraeli 1948). Having fashioned his trajectory – of how energetic Victorian emprise degenerated into post-industrial inertia – Wilson meshed his big picture with the small when, in Gee’s documentary on Joy Division, he led off, ‘I don’t see this as the story of a rock group. I see it as the story of a city’, adding, ‘The revolution that Joy Division started has resulted in this modern city… The vibrancy of the city and all the things like that are the legacy of Joy Division’, referring finally to ‘The story of the rebuilding of a city that began with them.’ This eschatology is endorsed by Gee’s ‘scriptwriter’ – though there is no script – Jon Savage, who has written an essay to support the documentary in the Spring 2008 edition of Critical Quarterly, where his rather rambling discourse is there to back the inclusion of bleak grey photographs he took of Manchester buildings in 1977 (Savage 2008). It seems the sun never shone when Savage was around.Conversely, let us shine a light on the facts. In the Manchester-Salford complex a period of avid metropolitan modernist planning took place in the 1950s and 1960s, with the objective, first laid out in the 1945 City of Manchester Plan, to eradicate a Victorian heritage of unplanned urban sprawl, one turned to further disarray by momentous wartime damage, and due to which Manchester lacked a vivid civic identity. Instead, the corporation planned a circle of satellite towns in the ‘garden city’ style of 1930s Wythenshawe, the hub for which would be an entirely regenerated city centre of impressive modern offices and prominent civic amenities, a flagship city to compete with other second cities like Chicago, Manchester’s model (HMSO 1995, 11-20).

Meanwhile the post-war pressure for council housing, and the lack of cash and resources had led, instead of garden cities, to a huge inner-city demolition programme. It started in 1954 in parallel with the hurried construction of overspill estates such as Hattersley and Langley (HMSO 1995, 24). Yet the re-housing schemes moved too slowly to meet both national and local objectives. Pressure to find cursory solutions was applied both by Conservative (1951–64) and Labour regimes (1964–70). In the conurbation the Corporation was coerced to produce a hassled second phase outlined in the 1961 Development Plan. Out of this sprouted those inner-city modernist monsters Fort Ardwick, Fort Beswick and the Hulme Crescents, all completed by 1972 and so hastily built that within two years many of the units were uninhabitable (Shapely 2006, 73).

Nevertheless, from the start of the modernist development of Manchester in the middle 1950s ¬until the post-modern shift in the mid-1970s, the vigorous scale of post-war neo-modernist commercial and institutional building resulted in twenty-five major modernist concrete, glass and steel buildings planned and built for the city complex. Table 2 lists these, starting with the surreal ‘Toast Rack’ domestic science college of 1958 (designed by a local civic architect), progressing through the Towers – such as the iconic Co-op of 1962, Owen’s Park 1964, Moberley 1965 and the Maths Tower of 1968 – to the Royal Exchange’s spectacular ‘space pod’ of 1976. This list is not inclusive and excludes, for example, the Arndale Centre, a massive but protracted and piecemeal retail development of the 1970s that was completed only in 1980.

Nevertheless, from the start of the modernist development of Manchester in the middle 1950s ¬until the post-modern shift in the mid-1970s, the vigorous scale of post-war neo-modernist commercial and institutional building resulted in twenty-five major modernist concrete, glass and steel buildings planned and built for the city complex. Table 2 lists these, starting with the surreal ‘Toast Rack’ domestic science college of 1958 (designed by a local civic architect), progressing through the Towers – such as the iconic Co-op of 1962, Owen’s Park 1964, Moberley 1965 and the Maths Tower of 1968 – to the Royal Exchange’s spectacular ‘space pod’ of 1976. This list is not inclusive and excludes, for example, the Arndale Centre, a massive but protracted and piecemeal retail development of the 1970s that was completed only in 1980.However, many of the new concrete, steel and glass commercial and institutional buildings were neither varied nor coordinated enough to withstand public disapproval, a notorious example being the complex around the Maths Tower, the Precinct Centre, and the Royal Northern College, where the ‘streets in the sky’ walkways were designed at different heights and so couldn’t be connected up. Thus, contrary to the view promoted in the Factory story, the image that Manchester presented to the world was not of a derelict city but a comprehensively modern one – that had got it wrong. In fact, those were the words that Cllr. Allan Roberts, chair of Manchester Council’s Housing Committee expressed in 1977, adding, ‘Manchester’s not been doing its job’. He admitted this after being cornered by burgeoning sets of tenants’ action groups whose campaigns, and the Council’s reactions, are well documented in Peter Shapely’s essay for the journal Social History (Shapely 2006).

The newly formed metropolitan county, the Greater Manchester Council of 1974, identified a clear solution, which materialised as the default post-modern architectural reaction of the period translated to the housing, amenities and image needs of the conurbation: that is, conversion of existing buildings rather than their demolition, identifying conservation areas such as Castlefields, marketing notions of legacy, pedestrianising the city centre, and making the initial attempts within the city of caging modernism within a bricked heritage, firstly and most sensationally at the Royal Exchange Theatre in 1976, and, in that sense following on, the Haçienda of 1982 and, nearby it, both the Cornerhouse visual arts centre and the Greenroom Theatre of 1983. In other words, Factory’s nightclub represented a commercial contribution to a public post-modern design project.

In terms of cityscapes and epochs, then, it appears to be in this post-modern context that we must place the birth of The Fall. Yet if we do so we slip into the same trap in which the Factory story has found itself caught. It is a coarse and quixotic determinism that conjures up the grids and correspondences needed to bond building sites and bands, civic plans and popular songs in the way that the Factory faction has done. The Fall certainly emerged – as did Joy Divison – from a set of circumstances tied to urban environment and class, but not wreckage and squalor. And in strictly musical terms we find in the births of these bands continuities from beyond the punk scene, such as Ian Curtis’s ‘German’ look and Smith’s Beat style (the bass of The Fall’s founder, Tony Friel, was called Jaco, after the jazz bassist Pastorius). Nevertheless, if we are to test whether Factory’s modernist claims suit the times, we must check how far a modernist aesthetic was already present in the city’s music scene. We can indeed identify bands spawned in the area at the time of the late 1960s that were progressive, utopian and internationalist in tendency: Barclay James Harvest, Van der Graaf Generator, 10cc. The short mid-1970s punk scene was definitely a cartoon-like negation of groups like them. But in reaction to that, the effervescent post-punk scene was in general more integrative, tending to mesh convention – such as song form – with experimentation, and to link punk’s gestural Luddism with a progressive curiosity for technology and sound production (on stage and in the studio). In the end it might be claimed that Van Der Graaf Generator’s appearance at University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology on 8 May 1976 was more influential to local post-punk aesthetics than the Sex Pistols’ two gigs at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on 4 June and 20 July of that year, (see Nolan 2006).

In terms of cityscapes and epochs, then, it appears to be in this post-modern context that we must place the birth of The Fall. Yet if we do so we slip into the same trap in which the Factory story has found itself caught. It is a coarse and quixotic determinism that conjures up the grids and correspondences needed to bond building sites and bands, civic plans and popular songs in the way that the Factory faction has done. The Fall certainly emerged – as did Joy Divison – from a set of circumstances tied to urban environment and class, but not wreckage and squalor. And in strictly musical terms we find in the births of these bands continuities from beyond the punk scene, such as Ian Curtis’s ‘German’ look and Smith’s Beat style (the bass of The Fall’s founder, Tony Friel, was called Jaco, after the jazz bassist Pastorius). Nevertheless, if we are to test whether Factory’s modernist claims suit the times, we must check how far a modernist aesthetic was already present in the city’s music scene. We can indeed identify bands spawned in the area at the time of the late 1960s that were progressive, utopian and internationalist in tendency: Barclay James Harvest, Van der Graaf Generator, 10cc. The short mid-1970s punk scene was definitely a cartoon-like negation of groups like them. But in reaction to that, the effervescent post-punk scene was in general more integrative, tending to mesh convention – such as song form – with experimentation, and to link punk’s gestural Luddism with a progressive curiosity for technology and sound production (on stage and in the studio). In the end it might be claimed that Van Der Graaf Generator’s appearance at University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology on 8 May 1976 was more influential to local post-punk aesthetics than the Sex Pistols’ two gigs at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on 4 June and 20 July of that year, (see Nolan 2006).Existent co-ordinates in the mid-Seventies air informed this post-punk integrative disposition. One such co-ordinate was the resurgent folk music scene of that time, through which singer-comedians such as Mike Harding and Bob Williamson propelled the Lancashire accent. Yet the conscious assertion of a local lingo, in line with the emergent promotion of a heritage culture, turned to deep embarrassment amongst progressive minds with the national success in April 1978 of Brian and Michael’s glutinous homage to local painter L.S. Lowry, ‘Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs’, and, while Ian Curtis of Joy Division maintained his affected American brogue in order to summon ghosts, others, like Mark E. Smith, gradually adopted ironised or embroidered accents, not in order to ‘represent’, but to stress the exceptional act of performance. Nevertheless, in 1978, Paul Morley would excitedly review in the New Musical Express (NME) a Manchester Musicians’ Collective gig under the headline, ‘These are the Mancunion Mancunions’, (see Morley 1978)

And when the conurbation started to re-assess its matchstalk inheritance it found, inside its dilapidated warehouses, post-punk musicians already there, practising. In ‘renting the heritage’, they were doing little for their health in those dank, freezing echo chambers, but they were working there together in order to prepare for gigs in old buildings such as The Squat (a derelict music college) or dishevelled clubs with dog-eared music licenses such as the Cyprus Tavern and the Russell Club. Rehearsal rooms, 4-track studios such as Graveyard and Revolution, the ‘gentle giant’ tour manager Chas Banks, Oz PA Hire, promoter Alan Wise and Rabid Records were all part of the micro music industry that sprang up in a state of alternative enterprise, in which Factory acted out the role of Icarus. It was New Hormones, run by the non-Mancunion Richard Boon, that did succeed and which gave The Fall its start in a recording studio. Factory was not the brightest thread in the skein of yarns spun about those times.

And when the conurbation started to re-assess its matchstalk inheritance it found, inside its dilapidated warehouses, post-punk musicians already there, practising. In ‘renting the heritage’, they were doing little for their health in those dank, freezing echo chambers, but they were working there together in order to prepare for gigs in old buildings such as The Squat (a derelict music college) or dishevelled clubs with dog-eared music licenses such as the Cyprus Tavern and the Russell Club. Rehearsal rooms, 4-track studios such as Graveyard and Revolution, the ‘gentle giant’ tour manager Chas Banks, Oz PA Hire, promoter Alan Wise and Rabid Records were all part of the micro music industry that sprang up in a state of alternative enterprise, in which Factory acted out the role of Icarus. It was New Hormones, run by the non-Mancunion Richard Boon, that did succeed and which gave The Fall its start in a recording studio. Factory was not the brightest thread in the skein of yarns spun about those times.Much of the city music scene, even Factory through its proclivity for Situationism, was driven by political critique, and in the experience of many the most class-conscious of all of the bands was The Fall. It always passed a common litmus test for the worth of a band at the time: would it play for free for Rock Against Racism? It would, but Mark E. Smith and Una Baines often stressed that what they believed in formed the content of their work and was not to be confined to a slogan on a banner, for The Fall was critical of both the state we were then leaving and the state that was arriving, and it has remained an agent of broad (as well as picky) critique, the general target of which is, as Smith put it as recently as 26 April 2008 to the Daily Telegraph, ‘the threat of some kind of standardised horrible society run by a bunch of fucking wankers’ (Blincoe 2008).

The vigour and width of this critique surely explains the richness of the material produced in the music and also in the lyrics, and accounts for its range between simplicity (‘Repetition’) and density (‘Spectre versus Rector’), which informs the entire wayward output of the last thirty years. I emphasise music here because composer Trevor Wishart and I in the Manchester Musicians’ Collective loved the music of the band, especially the dissonance achieved through three means – tuning, bitonality, and looseness of co-ordination. The understandable tendency for reviewers to focus on Mark’s lyrics unduly subordinates the sound world in which they’re set, and discounts the musicians who contribute so much to the fabric of the experience. After all, The Fall is a band that plays songs. What fascinated Trevor and me was the way that those songs were not so much constructed as discovered, realised by the members working out through time random ideas that were connected only by the presence of the people in the room at that moment.

The vigour and width of this critique surely explains the richness of the material produced in the music and also in the lyrics, and accounts for its range between simplicity (‘Repetition’) and density (‘Spectre versus Rector’), which informs the entire wayward output of the last thirty years. I emphasise music here because composer Trevor Wishart and I in the Manchester Musicians’ Collective loved the music of the band, especially the dissonance achieved through three means – tuning, bitonality, and looseness of co-ordination. The understandable tendency for reviewers to focus on Mark’s lyrics unduly subordinates the sound world in which they’re set, and discounts the musicians who contribute so much to the fabric of the experience. After all, The Fall is a band that plays songs. What fascinated Trevor and me was the way that those songs were not so much constructed as discovered, realised by the members working out through time random ideas that were connected only by the presence of the people in the room at that moment.It is for this reason that I persist in calling The Fall a band, meaning that a band is a team of musicians singled out by a corporate name. The individual identities of the musicians contribute to the integrity of the overall sound, but those identities are of less interest than the aural result. A band is closer to, say, Manchester’s Hallé Orchestra, which will take in deputies and visiting players, while the audience, so long as expectations are satisfied, will consider it’s heard the Hallé at 100%, not 90%. Conversely, I consider a group to be an assembly of named personalities, who work together but may individually harbour creative ventures. When a group loses a member, it often has difficult in finding a replacement who will satisfy an audience of the group’s fresh integrity. Perhaps The Rolling Stones was the first British rock band to become a group, prompted by the maverick behaviour of Brian Jones, while The Fall is a band that’s stayed a band. A tension arises between a band mediated as an entity and the needs of the media to attend to it within the conventional expressions of personality. The person in a position to assume identity on behalf of the band is not necessarily the one in control but the one who can most directly presume authority.

Control is achieved because the band is an entity (as one thing) and it can therefore be framed conceptually (as one thing), and it is through this framing that power is claimed and asserted. In a band it is commonly the person physically closest to the public, the one who takes and needs the least internal co-ordination, the fewest cues.

Control is achieved because the band is an entity (as one thing) and it can therefore be framed conceptually (as one thing), and it is through this framing that power is claimed and asserted. In a band it is commonly the person physically closest to the public, the one who takes and needs the least internal co-ordination, the fewest cues. Smith has alleged in his 2008 autobiography, that ‘They [the band] didn’t want to be in The Fall. The whole concept of The Fall back then was mine. They didn’t get it. The audience did, but not them’ (Smith 2008, 46). In fact its bass player, Tony Friel, started The Fall in 1976. Friel resigned on a matter of principle around Xmas 1977 when Mark introduced his new girlfriend, Kay Carroll, as the band’s manager. The result was that the singer took control, turning a once collective venture into a business enterprise under his leadership.

It is this sense of entrepreneurism that most chimes with Manchester’s recent history, one which might be crudely termed the Thatcherisation of the city. Manchester’s Labour-led administration was a target of the (1979–1990) Thatcher government’s plan Streamlining the Cities (1983) which resulted in the 1986 abolition of the Greater Manchester Council and in its place a directive to elevate economic dynamism through the privatisation of resources which in turn would generate competition in services, a formulation known as ‘entrepreneurial urbanism’ (Ward 2003, 116; Williams 2003, 53- 56). This was a move from government to governance, an ideology that New Labour in power (1997–) persisted with as eagerly as the Conservatives (1979–1997). But it was also designed to impel an assertive urban consumption economy, one which measured prosperity by possessions and which emerged forcefully through the flowering of two related reactionary phenomena in the late 1980s and 1990s – ‘Madchester’, ‘laddism’ – focussed around the leisure market, mainly in football, alcohol and drugs, and epitomised in the local music scene first by Factory’s band The Happy Mondays and then supremely by Oasis. Tickell and Peck point out how the privatising shift of power from elected local authorities to business-led bodies led to the naturalisation of male power ‘as the legitimate conduit for effective local governance’ (Tickell & Peck 1996, 595), signifying how far the story of the Manchester conurbation’s apparent resurgence may be read as a reversionary one. There are no happy women in the Factory story.

Indeed, a return to aggressive neo-modernism that so strongly symbolised rejuvenation and success for the Manchester conurbation may explain the surge of high-rise concrete and glass buildings around the city complex, a style derided by Smith as ‘glorified fridge boxes’ (Smith 2008, 98). Most noticeable among them is the 47-storey Beetham Tower (2006) and Great Northern Tower (2007) among a quasi-modernist resurgence of civic and business showpieces that followed in the wake of the IRA bombing of the Arndale Centre in 1996. The picture is somewhat complicated by, firstly, the introduction of urban grant-aid from the European Union (Bridgewater Hall, 1996) and the advent in 1993 of the National Lottery, which, as a result of campaigns by the architecture profession, offered millions of pounds for new building in sport, heritage and the arts, benefiting major projects in East Manchester and Salford Quays such as the Lowry Centre (2000) and the Imperial War Museum North (2002). Overall, then, Manchester has returned to its modernist mission after a post-modern digression of which Factory played a part. Whether this time the conurbation has got it right rather than wrong, it is too early to say.

Indeed, a return to aggressive neo-modernism that so strongly symbolised rejuvenation and success for the Manchester conurbation may explain the surge of high-rise concrete and glass buildings around the city complex, a style derided by Smith as ‘glorified fridge boxes’ (Smith 2008, 98). Most noticeable among them is the 47-storey Beetham Tower (2006) and Great Northern Tower (2007) among a quasi-modernist resurgence of civic and business showpieces that followed in the wake of the IRA bombing of the Arndale Centre in 1996. The picture is somewhat complicated by, firstly, the introduction of urban grant-aid from the European Union (Bridgewater Hall, 1996) and the advent in 1993 of the National Lottery, which, as a result of campaigns by the architecture profession, offered millions of pounds for new building in sport, heritage and the arts, benefiting major projects in East Manchester and Salford Quays such as the Lowry Centre (2000) and the Imperial War Museum North (2002). Overall, then, Manchester has returned to its modernist mission after a post-modern digression of which Factory played a part. Whether this time the conurbation has got it right rather than wrong, it is too early to say.If my remark about Thatcherization and entrepreneurism suggests that Smith is a free market kind of guy, then it needs correcting. He criticised the selfishness of her era, arguing, ‘Thatcher’s an antagonist… but people voted her in for their own greed, all looking at rewards’ (Ford 2002a, 97). Yet he supported that side of Thatcher’s project that promoted an ethic for gainful work as a personal obligation, as opposed to a unionised one (an undeniable irony in Thatcher’s case, as her policies were the cause of dramatically high unemployment). In his autobiography he declares: ‘The more you make of your life, then the more you fucking do… Thomas Carlyle, the Scottish writer, said, “Produce, produce – it’s the only thing you’re there for.” This is what I’m talking about’ (Smith 2008, 32). Smith adds that he has a ‘very desk-job attitude’ to The Fall (Smith 2008, 32). Here the ideological link is rooted more to ‘old’ Labour principles which through its very title promotes the centrality of the concept of productive endeavour.

Above all Smith embodies the ‘Old’ working class disposition of the autodidact, who, as Bourdieu states, ‘has not acquired his culture in the legitimate order established by the educational system’ and is ‘fundamentally defined by a reverence for culture which was induced by abrupt and early exclusion’ (Bourdieu 1984, 328). And in his splendid account of British working class intellectual life, Jonathan Rose adds that in order ‘to become individual agents in framing an understanding of the world’ autodidacts ‘resisted ideologies imposed from above.’ (Rose 2001, 12) They did so, as did Smith, by reading and arguing, and out of the reading came the writing. Smith’s interest in esoterica reflects autodidacticism, and his late-teen discovery of another performing/writing Smith, Patti – together with the general rehabilitation at that time of her Beat forebears, such as William Burroughs whose cut-up technique inspired the Lancashire Smith – came about just as a resurgence of radical individual anarchism superseded communal leftist campaigning such as Rock Against Racism. He is not quite the Manchester one-off he is portrayed: the wonderful cartoonist Ray Lowry and cyber-novelist Jeff Noon spring to mind, in those days good drinkers like Smith. Yet his achievement in gathering information, gaining knowledge, and placing it imaginatively back into public space is undeniable, while his lyrics that comment on and describe issues around mental health, linked to the patients he knew at Prestwich Hospital, are unique and significant. Smith’s approach is doubtless informed by the way post-war Beat ideology dismissed modernist utopianism and replaced it with a voyeuristic interest in the ‘real life’ routines of the outlawed and the disenfranchised. The Beat aesthetic further accounts for The Fall’s confluence of experimentation (a very Beat ‘living the moment’) with its default garage band style, one clearly influenced by The Velvet Underground, another Beat-influenced band that chopped and changed its members.

Above all Smith embodies the ‘Old’ working class disposition of the autodidact, who, as Bourdieu states, ‘has not acquired his culture in the legitimate order established by the educational system’ and is ‘fundamentally defined by a reverence for culture which was induced by abrupt and early exclusion’ (Bourdieu 1984, 328). And in his splendid account of British working class intellectual life, Jonathan Rose adds that in order ‘to become individual agents in framing an understanding of the world’ autodidacts ‘resisted ideologies imposed from above.’ (Rose 2001, 12) They did so, as did Smith, by reading and arguing, and out of the reading came the writing. Smith’s interest in esoterica reflects autodidacticism, and his late-teen discovery of another performing/writing Smith, Patti – together with the general rehabilitation at that time of her Beat forebears, such as William Burroughs whose cut-up technique inspired the Lancashire Smith – came about just as a resurgence of radical individual anarchism superseded communal leftist campaigning such as Rock Against Racism. He is not quite the Manchester one-off he is portrayed: the wonderful cartoonist Ray Lowry and cyber-novelist Jeff Noon spring to mind, in those days good drinkers like Smith. Yet his achievement in gathering information, gaining knowledge, and placing it imaginatively back into public space is undeniable, while his lyrics that comment on and describe issues around mental health, linked to the patients he knew at Prestwich Hospital, are unique and significant. Smith’s approach is doubtless informed by the way post-war Beat ideology dismissed modernist utopianism and replaced it with a voyeuristic interest in the ‘real life’ routines of the outlawed and the disenfranchised. The Beat aesthetic further accounts for The Fall’s confluence of experimentation (a very Beat ‘living the moment’) with its default garage band style, one clearly influenced by The Velvet Underground, another Beat-influenced band that chopped and changed its members. Mention of the Velvets connects The Fall with Joy Division, which the Factory story does not permit, although Ian Curtis was almost as much the autodidact as Smith. The Factory story so flattens Manchester that only the Factory and its tenants are left standing. Yet, as Wilson’s beloved Situationists declared, ‘Beneath the pavements – the beach!’ It is through the rubble of what is left, once the Factory story has been foisted on us as the received narrative, that The Fall and the others will provide, as an alternative, the richest, most potent, most kinetic history of that city. As I said, this is the worst possible reason for writing about The Fall, and so I am sorry for wasting your time.

References

Bourdieu, P. ([1979] 1984), Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Translated by R. Nice, (London: Routledge).

Blincoe, N. (2008), ‘Mark E Smith: Wonder and Frightening’, Daily Telegraph

Carlyle, T. ([1832] 2000), Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Champion, S. (1990), And God Created Manchester (Manchester: Wordsmith).

Disraeli, B. ([1848] 1948), Coningsby, or the New Generation (London: London Edition).

Ford, S. (2002a), Hip Priest: the story of Mark E. Smith & The Fall (London: Quartet Books).

____, (2002b), ‘Primal Scenes’, The Wire, No. 219, May, 28-33.

Hetherington, K. (2007), ‘Manchester’s URBIS’, Cultural Studies, Vol. 21, Nos 4-5, September, 630-649.

HMSO (1995), Manchester, Fifty Years of Change: Post-War Planning in Manchester (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office).

Morley, P. (1978), ‘These are the Mancunion Mancunions’, NME, 1 September, 25.

Nolan, D. (2006), I Swear I Was There: The Gig That Changed the World (Church Stretton: Independent Music Press).

Rose, J. (2001), The Intellectual History of the British Working Classes (London: Yale University Press).

Savage, J. (2008), ‘The Things That Aren’t There Anymore’, Critical Quarterly Vol. 50, Nos.1-2, 180-197.

Shapely, P. (2006), ‘Tenants Arise! Consumerism, Tenants and the Challenge to Council Authority in Manchester, 1968-92’, Social History, Vol. 31, No.1, 60-78.

Smith, M. E. (2008), Renegade: The Life and Tales of Mark E. Smith (London: Viking).

Tickell, A. & Peck, J. (1996), ‘The Return of the Manchester Men: Men’s Words and Men’s Deeds in the Remaking of the Local State’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 21, No. 4, 595-616.

Wilson, A. (2002), 24 Hour Party People: What The Sleeve Notes Never Tell You (London: Channel 4 Books).

Ward, K. (2003), ‘Entrepreneurial Urbanism’, Area, Vol. 35, No. 2, 116-127.

Williams, G. (2003), The Enterprising City Centre: Manchester’s Development Challenge (London, Taylor & Francis).

Relevant article